I’m an engineer by trade, which means that my life consists of a constant barrage of questions that normal people consider to be neurotic. “What’s wrong with this? When can you have it fixed? Why can’t you have it fixed sooner? Why did this go wrong? What should you have done to prevent it from going wrong? Why didn’t you pay attention to see that it could go wrong and do something about it before this happened?” The underlying assumption behind all the questions is the same: the outcome isn’t what it should have been; it’s all your fault, and you can do better.

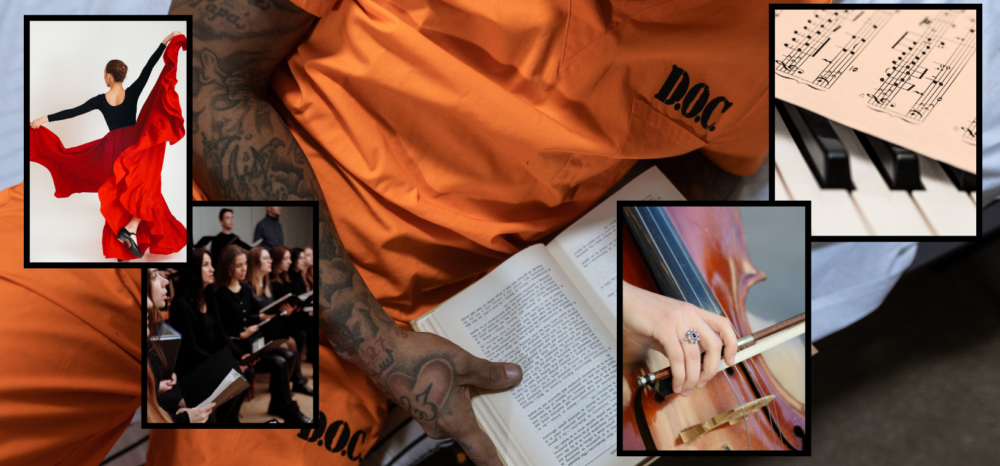

Here’s my dilemma. KnoxCAM comes into facilities once a year, we do our little dance, sing our little songs, pack our things, and then leave. I don’t know how many inmates (if any) come to Christ, but if even one doesn’t, the questions start, as well as the assumptions that go along with it. We (I) weren’t outgoing enough. We (I) didn’t smile or have the proper demeanor. The material was shoddily done, etc.

What’s even worse is the knowledge that, no matter how hard I try, there are some factors that I have absolutely no control over. Some men are there just to see the goofy people who’ve come to play the great white hope, and they want some amusement at our expense. Some can’t think of anything better to do, so they come to get out of their cells for a little while. The infernal ballasts in the gyms hum so badly that everyone has trouble hearing what’s going on, and the sound tech pulls out what’s left of his hair. Some facilities won’t even let us speak with any inmates after we finish for security reasons. No matter which one happens, and it’s usually more than one, the voices start. “You incompetent dolt, they’re going to hell, and it’s your fault…”

At times like these, I have to re-adjust my definition of success. The world defines success as “getting things done”. (Seriously, that’s one of the “core values” at my job.) We want numbers. Make that widget work, crank out that product, “grab that cash with both hands and make a stash” (Roger Waters). That’s not God’s definition of success. God calls people successes that the world regards as absolute failures, and vice versa. Moses spent forty years in self-imposed exile, having thrown away all the prestige and power of Egypt to herd sheep in the middle of nowhere. Jeremiah is the Bible’s version of the Greek legend of Cassandra, always prophesying truth, but never believed. Most of the apostles died horribly painful deaths at the hands of the most powerful empire the world had ever seen up to that point, which couldn’t care less about some hick rabbi from the middle of nowhere, as long as you affirmed that Caesar was a god.

Mother Theresa summed it up by noting that God calls us to be faithful, not successful. The Old Testament saints all died looking forward to the promises of God, but having little clue how they would be fulfilled. Time and time again, God calls his people to do things that the world regards as silly for people the world regards as worthless. Who knows how it will turn out? I don’t, and I don’t have to. I just have to be faithful. I worry about results too much. That’s the business of the Holy Spirit. The Bible is chock full of incompetent dolts whom God uses to do amazing things.

You could say that prison ministry is an insult to my world-reinforced arrogance. I suppose that it is, but I prefer to think of it as a much-needed dose of sanity. Pretending to be omnipotent is exhausting.